Greenwashing Texans:

How Companies wrap harmful agendas with environmental Rhetoric

The Illusion of Sustainability

Greenwashing is the practice of companies presenting themselves as environmentally responsible while engaging in practices that harm ecosystems, communities, and long-term sustainability. In Texas and beyond, corporations are increasingly using this tactic to push extractive or exploitative agendas under the guise of conservation. At its core, greenwashing is a calculated strategy. By aligning their language and branding with popular environmental ideals, companies seek to deflect criticism and attract public or political support. The terms “sustainable,” “conservation,” and “green” are used as marketing tools, regardless of whether the practices behind them live up to those labels. In many cases, the harm caused by these projects is difficult to detect immediately, making the misdirection even more effective. One prominent recent example involves a groundwater extraction project cloaked in the language of aquifer recharge and ecological benefit. The public messaging emphasizes stewardship, water replenishment, and green infrastructure — but a closer look reveals a plan designed primarily for private gain, with significant risks to aquifers and rural communities.

The "Sandwich technique"

One effective tactic used in greenwashing is what communication experts call the “sandwich technique”: placing a controversial or exploitative goal between two appealing, values-based messages. This structure builds trust before slipping in the real objective. This tactic has been studied extensively in marketing and political communication. It is designed to lull readers or listeners into agreement by first appealing to shared values, then introducing the controversial proposal, and finally reinforcing those values to leave a positive impression.

Example from Social Media

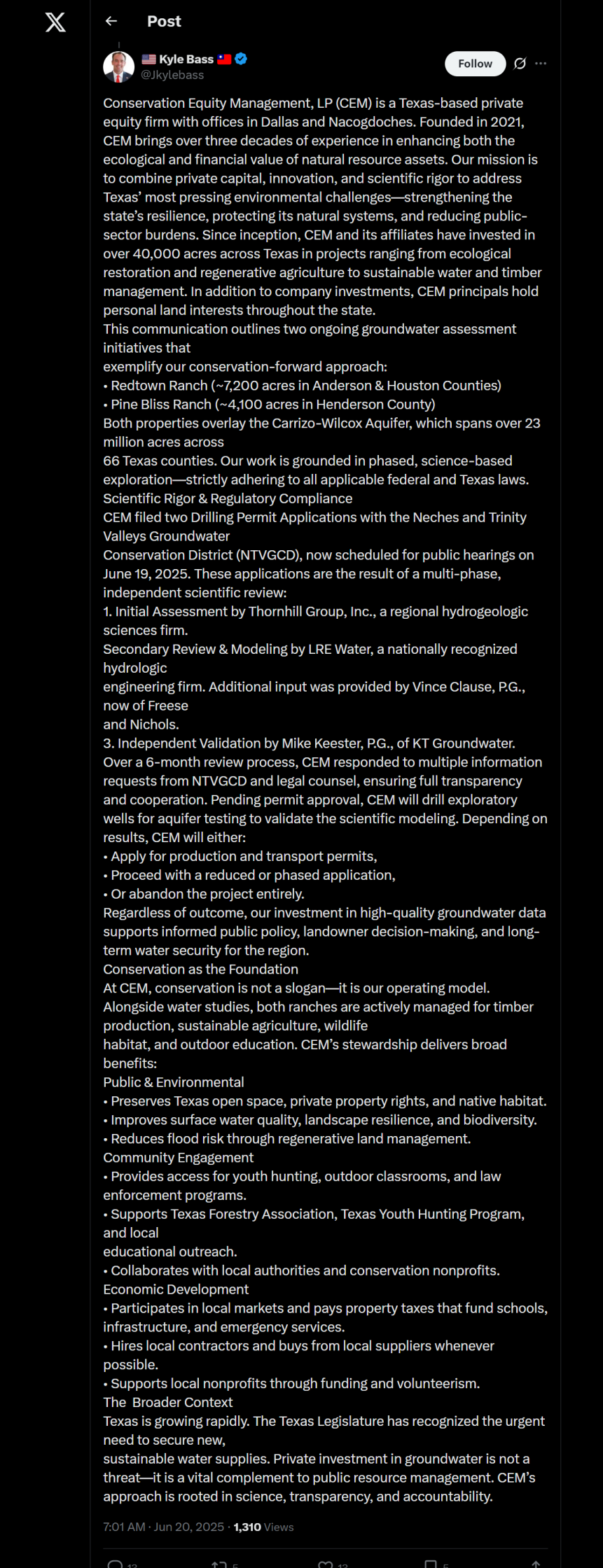

Kyle Bass, a hedge fund manager and executive behind a large-scale groundwater extraction effort in East Texas, demonstrated this technique in an X (formerly Twitter) thread. In a thread comment, Bass described Conservation Equity Management (CEM), stating:

“Our mission is to combine private capital, innovation, and scientific rigor to address Texas’ most pressing environmental challenges—strengthening the state’s resilience, protecting its natural systems, and reducing public-sector burdens.”

He followed this with the core announcement:

“CEM filed two Drilling Permit Applications with the Neches and Trinity Valleys Groundwater Conservation District… Pending permit approval, CEM will drill exploratory wells for aquifer testing to validate the scientific modeling. Depending on results, CEM will either: apply for production and transport permits…”

Then, he closed with more green framing:

“At CEM, conservation is not a slogan—it is our operating model… CEM’s stewardship delivers broad benefits: preserves Texas open space, private property rights, and native habitat. Improves surface water quality, landscape resilience, and biodiversity.”

This deliberate structure places an environmentally damaging goal — high-volume groundwater extraction — between lofty, conservation-forward language. It allows CEM to appear aligned with sustainability, even as it advances projects that could significantly impact regional water security.

The thread post concerning these projects was framed in optimistic language about sustainability, wildlife corridors, and science-based restoration. Bass emphasized that both Pine Bliss and Redtown Ranch overlay the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer and are managed with a “conservation-forward approach.” However, these environmental talking points are sandwiched around the true objective: securing groundwater drilling permits. It’s a strategy that allows resource extraction to wear the costume of restoration—appealing to both regulators and the public while concealing long-term ecological risk. The company markets its efforts as part of a mitigation banking initiative—claiming it will restore natural habitat and increase resilience. Yet the permit requests indicate industrial-scale groundwater pumping, with most wells exceeding 500 gallons per minute.

“Marketing is no longer about the stuff you make, but about the stories you tell.”

Seth Godin

What Experts Say

A United Nations article on greenwashing warns that:

“By misleading the public to believe a company or other entity is doing more to protect the environment than it is, greenwashing can erode public trust and delay urgent action.”

The article continues:

“While greenwashing may help a company’s bottom line in the short term, the long-term costs can be high — not only in lost credibility but also in lasting harm to the air and nearby waterways.”

This framing reflects the dangers of projects like the one proposed by CEM, where ecological risks are downplayed while the public is sold on the illusion of stewardship.

The language of sustainability can be misleading when it’s not backed by comprehensive data. For instance, if recharge efforts rely on rainfall or surface infiltration, but extraction occurs at much greater volumes than replenishment, the net effect is still groundwater loss — potentially irreversible in deep aquifer zones.

Additional research by Circle of Blue further supports this concern. They report that many groundwater-dependent ecosystems are in decline due to cumulative overpumping — often justified by projects claiming to be “net-zero” or “recharge-balanced.”

Dr. Peter Gleick, co-founder of the Pacific Institute, stated:

“Forty percent of our groundwater withdrawals are coming from unsustainable sources of water,” Dr. Gleick added. “This water provides a lot of our food. And we’re basically drawing down the bank account.”

The article also notes:

“The studies point out that the easy access to pumped wells has led to a surge of groundwater use for municipal, industrial and agricultural purposes over the past 50 years. While the surge has created economic gains, it has led to declining groundwater levels, lower pump yields, increased pumping costs, deteriorating water quality and damaged aquatic ecosystems.”

Legal and Policy Loopholes

Texas’s Rule of Capture allows landowners to pump virtually unlimited groundwater from beneath their property, regardless of the impact on neighboring wells or aquifer depletion. This 19th-century law has been challenged many times but remains largely intact, although local groundwater conservation districts (GCDs) can impose restrictions.

CEM and other private investment firms are increasingly taking advantage of this legal landscape. While they assert they are working within the law, the broader issue is one of ethics and sustainability. The regulatory framework does not currently account for cumulative impacts or the vulnerability of rural water supplies.

Many groundwater districts rely on Desired Future Conditions (DFCs) and Managed Available Groundwater (MAG) limits to manage water responsibly. However, when multiple companies each stay under their individual MAG limits but collectively exceed the safe threshold, the aquifer still suffers. This is a textbook example of what economists call the “tragedy of the commons.”

Even the Texas Water Development Board has acknowledged the difficulty in managing cumulative impacts of multiple permitted wells. In its 2022 State Water Plan, the board warns:

“While many strategies proposed by regional water planning groups address future needs, the development of these strategies could put additional pressure on groundwater supplies that are already being depleted in some areas.”

This concern is underscored in Chapter 6, which states:

“Groundwater levels in some areas of the state are projected to experience continued declines due to existing pumping and future demands.”

These admissions from a state agency confirm that Texas is already operating on thin margins. Yet private interests are seeking permits to expand extraction even further.

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

— Aldo Leopold

A Closer Look at CEM's Claims

Let’s break down some of the rhetoric used in Bass’s post:

- “Preserves Texas open space, private property rights, and native habitat” – These are classic greenwashing buzzwords. The project may preserve space on paper, but intensive groundwater extraction can disrupt ecosystems, lower surface water levels, and change land use over time.

- “Improves water quality” – There’s no evidence presented that pumping groundwater improves water quality; in fact, drawdowns can increase concentration of contaminants.

- “Provides access for youth hunting and outdoor classrooms” – This community-focused framing is intended to build goodwill, but it does little to offset ecological concerns about the aquifer’s long-term health.

Even when partnerships with conservation nonprofits are genuine, they can be used to divert attention from more pressing concerns. It’s essential for the public and oversight bodies to ask for full environmental impact assessments, not just highlights.

In addition, industry-funded science often lacks independence. While CEM cites a multi-phase review involving Thornhill Group and LRE Water, critics argue that these relationships may introduce bias, particularly when firms are paid by the applicant. Independent peer review and open data are critical for true accountability.

Importantly, many ranchers and farmers across Texas already engage in sustainable land management that does not require high-capacity wells. Conservation easements, rotational grazing, native habitat restoration, and soil health practices are all viable strategies that protect ecosystems and livelihoods without draining aquifers. Similarly, many of Texas’ most respected conservation areas operate effectively without tapping into high-volume groundwater sources.

The Broader Trend

What’s happening in East Texas is part of a broader trend across the U.S. and globally. As water scarcity increases due to population growth and climate shifts, groundwater has become a coveted asset. Hedge funds, private equity firms, and other financial players are moving into the water sector, acquiring rights and infrastructure with profit in mind.

From Arizona to California, similar concerns are emerging. In Arizona’s La Paz County, The Nature Conservancy has raised alarms over private interests purchasing farmland purely for the underlying water rights. And in California’s Central Valley, groundwater markets have emerged, often pricing out small farmers and threatening long-term ecological resilience.

While private investment can play a role in resource development, it must be held to rigorous public accountability standards. When firms act primarily in their own interest while cloaking their operations in environmental rhetoric, the consequences can be devastating — especially for rural residents, family farms, and ecologically sensitive areas.

Why It Matters

Greenwashing isn’t just a branding issue — it undermines real sustainability efforts, confuses the public, and allows extractive industries to operate without proper scrutiny. In the case of East Texas water, it could mean long-term damage to a finite and vital natural resource.

Communities in Henderson, Anderson, and Houston counties are already raising concerns about lowered water tables, well interference, and the transparency of the permit approval process. With the NTVGCD now reviewing permits submitted by CEM, the coming months could set a precedent for groundwater governance across the state.

Greenwashing also weakens the credibility of genuine environmental initiatives. When people become cynical or confused due to misleading marketing, they may disengage from real conservation work. It dilutes public trust and misdirects energy from solutions to spin.

What to Watch For

- Vague claims like “eco-friendly” or “sustainable” without evidence

- Projects that emphasize future benefits while ignoring current or cumulative harms

- Environmental partnerships or sponsorships that distract from core practices

- Industry-funded science or misleading metrics (e.g., acre-feet banked vs. impact on recharge zones)

- Overuse of terms like “conservation” to mask fundamentally extractive activities

Get Involved

Stay informed. Ask hard questions. Push for transparency.

Call your local representatives. Attend public groundwater hearings. Support truly sustainable agriculture, ranching, and water management initiatives. Demand real accountability, not just eco-friendly taglines.

The future of Texas water depends on our willingness to see through the green gloss and confront the true nature of these projects. Let’s not be fooled by packaging — it’s time to read the fine print and stand for real conservation.